Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO)

What Is a Patent Foramen Ovale?

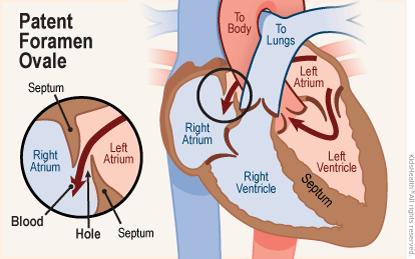

The foramen ovale (fuh-RAY-men oh-VAL-ee) is a normal opening between the upper two chambers (the right atrium and left atrium) of an unborn baby’s heart. The foramen ovale usually closes 6 months to a year after the baby’s birth.

When the foramen ovale stays open after birth, it’s called a patent (PAY-tent, which means “open”) foramen ovale (PFO).

A PFO usually causes no problems. If a newborn has congenital heart defects, the foramen ovale is more likely to stay open.

What Happens With a Patent Foramen Ovale?

Before birth, the foramen ovale allows blood flow to bypass the lungs (a fetus gets the oxygen it needs from the placenta, not the lungs). That way, the heart doesn’t work hard to pump blood where it isn’t needed.

When newborns take their first breath, a new flow direction happens. The blood now needs to go to the baby’s lungs. This new flow helps push the patent foramen ovale closed. The blood can no longer flow directly between the upper two heart chambers. Instead, it flows from the right side of the heart into the baby’s lungs to pick up oxygen, and then the left side of the heart sends the oxygen-rich blood out to the body.

In most people, the flap that closes off the foramen ovale gradually seals itself in place so it’s permanently closed. In babies, kids, and adults with a PFO, the flap remains unsealed.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of a PFO?

A PFO usually causes no problems, so most babies who have one don’t show symptoms. Many active adults have a PFO and don’t know it.

Sometimes having a PFO is helpful. Babies born with serious heart problems or pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs) and a PFO may have less severe symptoms because the PFO lets blood from the two sides of the heart mix.

What Causes a Patent Foramen Ovale?

A patent foramen ovale is normal until birth. The flap that closes it usually doesn’t completely do so until a baby is at least several months old. Why the flap doesn’t seal in some people is unknown.

Who Gets a Patent Foramen Ovale?

Everyone has them at birth, but the hole usually closes. PFOs that do not close are common, and found in 1 of every 4 adults. PFOs are more likely in newborns who have a congenital heart defect.

How Is a Patent Foramen Ovale Diagnosed?

A patent foramen ovale most often is seen on an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) being done for other reasons.

How Is a Patent Foramen Ovale Treated?

PFOs usually aren’t treated unless there’s another reason for heart surgery or someone’s risk for blood clots or stroke is higher than average.

A PFO may increase the risk of strokes because tiny blood clots elsewhere in the body can break loose and go to the heart via the blood. These tiny clots are usually filtered out of the blood by the lungs. In a person with a PFO, the clot can slip from the right atrium to the left atrium. From there, the clot goes to the left ventricle, which sends the clot out to the body or the brain, where it can affect organs that are much more sensitive to injury than the lungs. When a blood clot blocks blood flow to part of the brain, the result is a stroke.

Even in a person who has had a stroke, treatment usually focuses on preventing clots rather than closing the PFO. If closure is required, cardiac catheterization can be used to place a device through a long, thin tube guided through blood vessels to the heart to close the foramen ovale.

Looking Ahead

PFOs aren’t likely to cause trouble and need no special treatment for most people. But kids and adults should know that they have one if it is diagnosed.