An ATV accident turned a family vacation into a journey to save a young girl’s arm

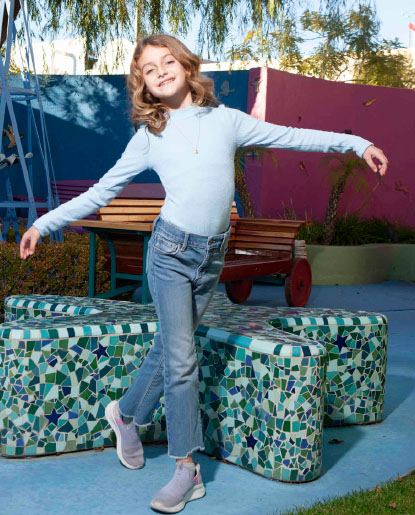

After an ATV accident, Elle received top-notch care by our plastic surgery team at Rady Children’s Hospital.

When the Ward family set off on a vacation to Northern California for the Independence Day holiday in 2021, they had no idea that the trip would take a terrifying turn.

On July 3, Ella Ward was a passenger in a six-seat ATV being driven by her father, Sam, when the ATV unexpectedly overturned, pinning the 8-year-old’s arm underneath the roll bar. While the rest of the vehicle’s occupants escaped unscathed, the ATV slid, injuring Ella’s arm even further, until three adults were able to turn it upright and get Ella to safety. What happened next was a whirlwind for the little girl and her parents, who were vacationing on a ranch an hour’s drive from the nearest children’s hospital.

“Ella’s arm was broken in between her wrist and elbow,” Sam recalls. “Not only that, but because of the movement of the ATV, she lost 50 percent of the muscle and 75 percent of the skin on her right forearm. So, along with the open broken bones, her arm was full of dirt, rocks and bacteria. It was mangled.”

An ambulance transported the family to a hospital in Fresno. When they arrived, Sam says, “there was a flood of doctors and they were all extremely concerned—they didn’t know how they were going to address it.”

Ella was rushed into surgery. The surgeon, who’d been in the military, told the Wards that his plan was to treat Ella as if she were a soldier with a war wound.

“That’s how bad it was,” Sam says. “He said, ‘I know how dangerous this is and I’m going to hit it hard and treat it for infection.’ That’s how they started—cleaning the arm, treating infection and performing lifesaving measures.”

At this point, the Wards and Ella’s doctors were unsure if they would be able to save her life, let alone her arm.

“I am certain that if this accident had happened in many other states, Ella would have died from the severity of her injury,” her mother, Lindsey, says. “In most places, her arm would have been immediately amputated. We didn’t know for a while if

hers would have to be—it was always

a possibility.”

Ella underwent several surgeries in Fresno while her medical team decided on the best course of action. Doctors cleaned her wound and put her bones together with titanium rods. Then, they searched for another team of experts to take over the remainder of the extensive care Ella was going to need to repair her nerves, muscle and skin.

Searching For Success In San Diego

A week after the accident, the Wards left Fresno to head home to San Diego and meet with Katharine Hinchcliff, MD, a plastic surgeon at Rady Children’s and an assistant clinical professor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine who specializes in reconstructive surgery, pediatric and adult upper extremity surgery and peripheral nerve surgery.

“They originally wanted us to go to Stanford, but when we told them we lived in San Diego, they found Dr. Hinchcliff. They interviewed her and felt that she would be even better at getting Ella’s hand to work again,” Sam explains.

The family drove back to San Diego with Ella medicated and with a special vacuum to drain the open wound on her splinted arm.

“She was like a china doll, she was so fragile,” Sam says. “We left without them being able to find her radial artery. She still had 50 percent muscle loss and most of her skin missing. But they said she had an 80 percent chance of keeping her arm.”

Still, Lindsey adds, “We were told that even if she kept her arm, there wouldn’t be any function.”

The Wards arrived at Rady Children’s with hope that Dr. Hinchcliff would have a plan not only to save Ella’s arm, but to help her regain as much function as possible. They quickly learned that with an injury as severe as Ella’s, with such a high risk of infection, the best plan is to have no plan at all.

“The most difficult thing for a kid with this type of injury is trying to give them and their family a realistic idea of the prognosis and picture ahead when you don’t know for sure what that’s going to be,” Dr. Hinchcliff says. “Trying to tell a concerned family what to expect is a skill we all develop and are continually working on as trauma surgeons.

“You don’t want to paint too rosy a picture and get a family’s hopes up,” she adds. “And you don’t want to paint too bleak a picture and have them give up hope. You have to put all the pieces of the puzzle and come up with a summation that’s not going to overwhelm them.”

Dr. Hinchcliff wasn’t able to devise a plan for reconstruction until she could evaluate Ella’s arm in the operating room. But despite the stress of not knowing what the future held, the Wards trusted that they were in the best hands with Dr. Hinchcliff and the team at Rady Children’s.

“Even before meeting her, we knew she was an incredible person just based on her experience—and she was,” Lindsey says. “She was incredible with her communication with us—we were able to reach her at any time—and treating us not just as patients, but as parents.”

Dr. Hinchcliff’s empathy made an impression on them, Lindsay says. “When you meet a lot of doctors, you realize some have empathy and some don’t. Dr. Hinchcliff does.”

Sam adds: “The first day we met her, she spent at least two hours with us. Then she came every day, for at least an hour, sometimes three hours. I asked her a million questions, and she answered every single one until I couldn’t think of any more to ask.

“Her bedside manner was absolutely over the top,” he continues. “She was candid about what happened, she was incredible at describing what she was going to do, and she told me to let her know the level at which I wanted to hear or see what Ella’s arm was like. I told her I couldn’t stomach it and I couldn’t mentally handle it, but if my kid had to handle it, I would, too.”

Enduring the Extreme

Over the next month that Ella was a patient at Rady Children’s, there was, in fact, a lot to handle. The first step was to find Ella’s radial artery, which sends oxygenated blood to the lower arm and the hand. “That first surgery was supposed to be a basic surgery, but it ended up being one of the most important,” Sam recalls.

Dr. Hinchcliff found the radial artery, which was fortunately still intact. She also evaluated the remaining muscles and tendons, debriding those that were not viable and connecting others to set the groundwork for future function.

“She gave that a 50/50 chance of succeeding,” Sam says, “and at the time we didn’t know how significant it would be.”

Finding the radial artery improved Ella’s candidacy for a muscle and skin transplant surgery, called a free tissue transfer, which could be used to replace the missing tissue in her arm. In this reconstructive technique, surgeons remove a piece of tissue from one site where it has a blood supply and connect the vessels feeding that muscle and skin to a blood vessel at another site. In Ella’s case, the donor site was the muscle in her upper left back, which was removed and attached to the injured area of her arm.

“The human body is nice in that it has a lot of spare parts and a lot of redundancies, so there are certain muscles you can do this with,” Dr. Hinchcliff explains. “The muscle we took from Ella’s back is a workhorse muscle in that it’s often used in scenarios like this where you don’t need them as intended.” Dr. Hinchcliff performed Ella’s surgery in conjunction with one of her partners from UC San Diego to ensure the surgery was safe and efficient. After surgery, Ella was transferred to the intensive care unit because the new muscle—which was completely exposed with only a small paddle of overlying skin—had to be continuously monitored.

“The ICU nurses were listening to her heartbeat for hours, making sure the transplanted muscle was receiving blood. If the blood flow to the muscle stopped, she would have had to go immediately back to the OR—it was critical to keep that muscle alive,” Sam says. “Essentially, for the next four days in the ICU, the job was to monitor that muscle.”

Ella also needed a blood transfusion. She was on a PICC line and an IV for medication, nutrition and liquids.

“She was a wreck,” Sam says. “Even though it was a successful surgery, we weren’t through the woods yet. We knew things could go south at any minute.”

Luckily, the muscle transplant took, and Ella could move forward to the next step: a skin graft that involved removing skin from her upper thighs and transplanting it to her arm. Once the graft was complete, the surgeons’ work was nearly done, but Ella’s was just beginning.

Download the full story below to continue reading: